(This article originally appeared in the January 1992 issue of SPIN.)

Return to your seats, buckle up, and say your prayers: Nirvana is on a collision course with the world. Nevermind, the band’s first major-label release, has exploded unexpectedly on the charts while the band’s public profile has expanded at a scary rate. With good reason. Remember the first time you heard a song or band that totally blissed you out? Well, this band takes you there. Nirvana lives up to its name—unless you don’t believe in bliss, in which case I feel sorry for you.

The album has already gone gold, and is even out-selling Guns N’ Roses double Use Your Illusion at some record stores. And the band’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” video garnered the world-premiere slot on MTV’s 120 Minutes, practically unheard of for a band that had never had a video shown before on MTV. Everyone seems to be reaching for Nirvana.

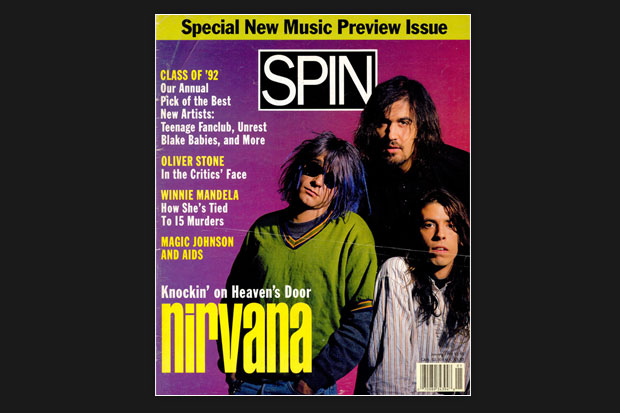

Guitarist—lyricist—possibly tormented guy Kurt Cobain, bassist—maniac—really towering guy Chris Novoselic, and drummer—Virginia native—seriously fun guy Dave Grohl are forging a mighty sound. Spawned in the Pacific Northwest, Nirvana’s music sounds like R.E.M. married to Sonic Youth, while having an affair with the Germs. Hole’s Courtney Love describes it thus: “Nirvana is plowing a new playground for all of us to play in.”

Success has come so quickly for the band that it has a tenuous handle on the realities of its rise to prominence. “I couldn’t even tell you shit like when Bleach [Nirvana’s first album, on Sub Pop] was released. I couldn’t even name the songs on the album,” says Cobain. “Our record-company bio is nothing but a huge lie. They wrote it up, but it was really lame—they called me at seven in the morning. In the end they just turned it over to us to write. So we made most of it up.”

“You know what I think is great?” interjects, Grohl. “The interviews in English magazines, because they sort of tidy up the grammar. You’re free to tidy up any of our grammar. Just make us sound smart.”

Nirvana was formed in 1987 by Aberdeen, Washington, native Kurt Cobain, who lived his formative years in a trailer park with his cocktail-waitress mom and didn’t listen to music until later in life. He hooked up with Novoselic, and they worked their way toward 1989’s Bleach, which was made in three days for $600 and crammed with nihilistic, punk-tinged melodic rock. The band toured, got a record deal with DGC, saw many bootleg releases hit the streets, picked up drummer Grohl in 1990 from D.C.’s punk-hardcore band Scream, toured in Europe with Sonic Youth, put out Nevermind, and will probably be touring for the rest of its born days. That is, until they all go into hiding to escape the glare of the spotlight.

Cobain has been mislabeled as a “spokesman for a disaffected generation.” He’s not interested in the job. His lyrics have a sheen of naiveté that just barely contains his anger—but gems like “I feel stupid and contagious / Here we are now, entertain us,” from “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” come off more as glimpses into his private world than rallying cries to the masses.

“I really have no desire to read the lyrics my favorite rock stars write,” says Cobain. “I don’t pay attention. My favorite album this year was the Breeders’ Pod [from 1990]. Actually, I lied—I do listen to Kim Deal’s lyrics. But I don’t really pay attention to what people write. Even interviews, I just take with a grain of salt. The only ones I’ve ever read that I really liked were ones with the Pixies and Butthole Surfers—other than that I can’t think of any that I even finished.”

When it comes to the band’s own interviews, Cobain says, “We lead such boring lives that we start to make up stuff.” But, as with any band that comes out of nowhere, stories will get made up anyhow. Example: A rumored contract signing with DGC for $750,000—which would have made it the largest indie signing in history—was, according to Cobain, “Journalism through hearsay. And then the numbers kept getting bigger so that a lot of people believed that we were signed for a million dollars.” In fact, the band says the deal was for $250,000 spread over two records.

“And now we’re snubbed by people who think we’re big rock stars,” says Grohl. “They think that when you get signed to a major label you get all this cash to spend.”

“I didn’t understand how the music business worked when I was young,” adds Cobain. “I used to curse the Butthole Surfers for having fifteen-dollar ticket prices. Now I obviously understand it more, but it’s just that with all these people paying attention it feels a little like being in the zoo. Maybe this could be the disclaimer article: What we’re gonna do now is let the kids know that we haven’t sold out.”

“Like, from now on all our shows are gonna be free,” says Grohl and laughs.

“And we’ll play with Fugazi for vegetable scraps,” says Cobain, only half joking. “We’re never going to lose our punk ethic.”

“We don’t want to be just lackeys to the corporate ogre,” laments Grohl.

They needn’t worry. Although there are a wealth of colorful stories concerning the band’s offstage shenanigans, Nirvana is hardly the product of record company-inspired, corporate rock-controlled rebellion. In other words, the band’s antics are not a ploy for headline-grabbing attention—it’s just the way they are. For instance, when MTV staged a pregig game of Twister in Boston between Nirvana, Smashing Pumpkins, and Bullet LaVolta, Cobain greased up Novoselic’s nearly nude body with Crisco oil after which the bassist used an American flag hanging on the wall to wipe himself off. “These jocks came up and were really bad-vibing me,” says Novoselic. “Like, ‘Hey, you don’t do that to our American flag.’ So I ended up having some kind of bodyguard go with me to the club.”

When Nirvana did a Tower Records in-store appearance this fall in New York, a plate of roast beef sandwiches was thoughtfully provided for the occasion, which gave rise to this potential quote of the year: “I thought these guys were an alternative band, but they’re eating meat.”

“Poseurs.”

There’s more. Cobain has thoroughly confused his record company by using multiple choice in the spelling of his name: Kurdt, Curt, and Kurt; Cobain or Kobain. Real and imagined stories run rampant of tour bus curtains being lit on fire, drunken backstage debaucheries, Grohl giving out Chris Cornell’s (actually Sub Pop’s) phone number during an on-air interview, their road manager’s being questioned in Pittsburgh because of a torched couch in the club, the band inviting hundreds of audience members onstage during a St. Louis show to escape the violent bouncers, and on and on.

Never mind the stories—to see is to believe. Live, these guys kick substantial ass. Nirvana shows are rife with churning, smashing, moving, sweaty ecstasy onstage and off. To witness the end of some sets is to understand why they cannot do an encore—there’s very little equipment left intact. They are adamant about playing only all-ages shows, to the point of adding an extra gig in Boston when they found out the show they performed at was not open to everyone. But they also pissed off a Philadelphia crowd by not doing an encore, provoking chants of “sellout.” With or without encores, at the end of the day Nirvana still gives it to its audience full force. It helps that the band members have had ample time on the road, because there the audience is your best friend—without them you’re totally on your own.

“Most of the time earlier on we’d stay at people’s houses that we’d just met,” says Cobain. “But I remember one time in Texas on our first tour we slept at the edge of a lake where there were signs all over saying beware of alligators. We all slept with baseball bats by our sides, or we tried to sleep. In the middle of the night we thought we saw one so we bagged out.”

Cobain’s got a tattoo on his arm. It’s the K Records symbol, representing the Olympia, Washington, indie label run by Beat Happening’s Calvin Johnson. This summer Johnson helped stage the International Pop Underground Convention, where, unlike other so-called new music conventions, they really did showcase only new talent, along with holding barbecues, parades, and disco dances. It’s very pure.

Cobain says, “It’s the event of the year. I vowed months ago that nothing was going to get in the way of me attending it—but unfortunately this year we missed it because we played the Reading Festival in England. But I’ve had the tattoo since last summer. It was a home job. Dave taught me.”

“You can do it with just a regular sewing needle, string, and some India ink,” instructs Grohl. “Wrap the thread around the needle, dip it in the ink, and jab it in.”

“But when I did it, the thread unraveled,” says Cobain. “So I ended up jabbing in the needle and pouring ink all over my arm.”

“Tips to keep yourself busy,” adds Grohl. Beyond home tattoos, Nirvana is waiting for the day when its record company, DGC, home to a slew of rock up-and-comers, holds a picnic so the band members can hang with its fellow labelmates—especially Nelson. Sonic Youth got a head start in the Nelson stakes when the band visited the blond boys on tour last year, but this trio has a bolder tribute in mind.

“Nelson have a room they go into before each show where they turn off the lights and meditate with incense burning,” Grohl says.

“So we’re gonna have the Nelson room where we burn effigies of them before we go onstage,” adds Cobain.

“Kinda like the Satan room,” Grohl concludes.

Obviously signing with a major has not put a stop to Nirvana’s fun. Instead, it has served the purpose of allowing more people to share the noise. Their T-shirts sum it up: The latest version proudly sports the slogan: kitty pettin, flower SNIFFIN, BABY KISSIN CORPORATE ROCK WHORES. Recently a DGC employee, who was wearing a “crack-smokin'” version of the shirt at a cash machine in L.A., was asked by the long arm of the law to turn the shirt inside out because it was offending passers-by.

To some of the great unwashed, Nirvana’s favorite bands remain obscurities: the Vaselines, a Scottish band whose tune “Molly’s Lips” often starts off Nirvana’s live sets, and the Japanese all- female pop trio Shonen Knife, who will be touring with them in Europe. And of course molasses-metal kings The Melvins—whose drummer Dale Crover played on Bleach‘s “Paper Cuts” and “Floyd the Barber” and did a brief stint on the road with them in the pre-Grohl period—hold a special place in their hearts.

“There is no band that changed my perspective of music like the Melvins,” says Grohl. “I’m not joking. I think they’re the future of music.”

“And the present and past,” adds Cobain. “They should get recognized for that.”

As Nirvana begins to plot out its quest for world domination, a scheme involving a certain metal-titan outfit is hatched.

“We’ll rub elbows with Metallica. That way they’ll wear our T-shirts and we’ll become an instant success,” says the forward-looking Cobain. Like they need any help.

On second thought, Cobain adds, “We’ve gotta get Kirk Hammett a Melvins T-shirt.”

“Yeah, because there’s nothing heavier than the Melvins,” says Grohl.